The forest falls silent as dusk settles. The canopy is pierced by golden streaks of light, flashing across the scales that glide soundlessly over the leaf litter. The forest pauses. The snake vanishes almost as quickly as it appeared—an ancient creature wielding a weapon that has shaped human fear for millennia.

That weapon—venom—is not the villain that countless tales have imagined. Modern research reveals something far more sophisticated: a biological mechanism sculpted by millions of years of evolution.

To understand venom is to understand the snake—and why coexistence may one day be our most rational choice.

A Library of Chemicals Written by Evolution

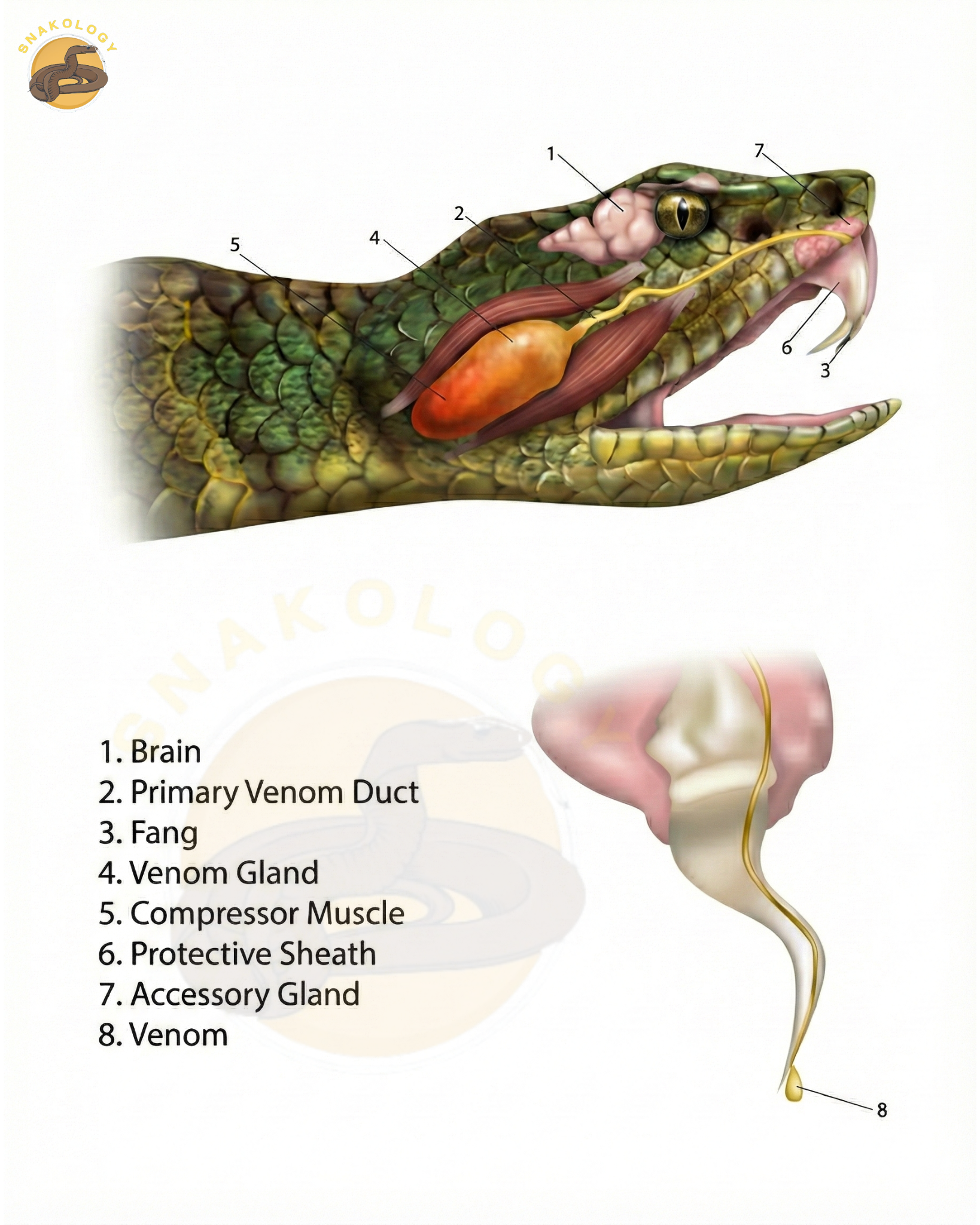

Inside a venom gland lies a microscopic universe: binding proteins, tissue-degrading enzymes, and peptide toxins that flip biological switches with astonishing precision.

This chemical arsenal is no accident. Two snakes may look nearly identical yet hold entirely different venom profiles, each adapted to their unique diet and ecological pressures. Venom is nature’s code—solving the world's oldest problem: eat or be eaten.

Working Synthesis: Venom in 3 Survival Strategies

In the brutal arena of predator and prey, venom acts as the ultimate equaliser, allowing small-bodied snakes to subdue prey far larger than themselves.

1. Neurotoxins: Severing the Signal

In cobras and coral snakes, neurotoxins interrupt nerve-to-muscle communication by blocking receptors such as acetylcholine. The result is paralysis—swift and decisive.

2. Hemotoxins: Dismantling from Within

Vipers deploy metalloproteinases that rupture blood vessels, disrupt clotting, and trigger extensive tissue damage. Visible swelling and bruising are surface signs of a profound biochemical assault.

3. Digestive Enzymes: Digestion Before the Bite

Some snakes begin digestion the moment they strike. Potent proteolytic enzymes weaken tissues, enabling the consumption of prey several times larger than the snake’s own head.

An Underutilised Self-Defense Weapon

Despite popular belief, snakes seldom waste venom on humans. Venom requires significant energy to produce. Defensive bites, if they occur at all, are often low-dose or entirely dry.

Myths That Bite Harder Than Snakes

- Myth: All venomous snakes are deadly.

Fact: Most bites are non-fatal with timely treatment. - Myth: Snakes chase people.

Fact: Field studies show snakes flee whenever possible; confrontation is a last resort. - Myth: Swelling means venom was injected.

Fact: Many defensive bites are dry and inject no venom at all.

Venom in Medicine: Nature's Plan for Healing

Antivenom: The Cure is in the Cause

Antivenom is created by immunising animals with trace venom doses, then purifying the resulting antibodies. When administered early, it can reverse severe envenoming.

Venom-Derived Medicines

- ACE inhibitors for hypertension originated from Brazilian pit viper peptides.

- Viper enzymes have inspired medical anticoagulants.

- Experimental therapies target cancer, chronic pain, and cardiovascular disease.

Learning to Live Safely Alongside Snakes

- Watch your step on grass, rocks, and leaf litter.

- Use a torch when walking at night.

- Give snakes the space to flee.

- Avoid handling or killing snakes; most bites occur during these attempts.

Why Understanding the Snake Saves Its Life

Snakes are often killed due to misunderstanding rather than danger. Their ecological importance is immense: regulating pests, stabilising food webs, and providing bioactive compounds for medicine.

Venom is not a curse but a masterpiece of evolution—one that deserves respect, not fear.